|

THE

WALL STREET JOURNAL.

Markets |

Heard on the

Street

Share Buybacks: The Bill Is Coming Due

U.S. companies borrowed heavily in recent years but often bought

back stock rather than investing in their business

|

Traders at the New York Stock Exchange Friday PHOTO: BRENDAN

MCDERMID/REUTERS |

By

Justin

Lahart

Feb. 28, 2016 1:46 p.m. ET

Low rates alone aren’t

enough to make it easy to pay off a loan. Many companies may find that

out the hard way, especially as high-yield debt markets show signs of

strain lately.

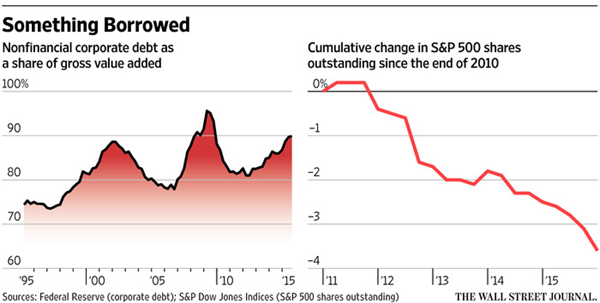

U.S. companies went on a

borrowing binge in recent years. Nonfinancial corporations owed $8

trillion in debt in last year’s third quarter, according to the

Federal Reserve, up from $6.6 trillion three years earlier. As a share

of gross value added—a proxy for companies’ combined output—corporate

debt is approaching levels hit in the financial crisis’s aftermath.

Most of the debt

increase came from bond issuance, as nonfinancial companies took

advantage of the

lowest rates on corporate bonds

since the mid-1960s. That is a plus as companies in many cases

extended the maturity of their debt and lowered borrowing costs.

The negative: Rather

than investing the funds they raised back into their businesses,

companies in many cases

bought back stock instead. That

was something that many investors welcomed, but it may have come with

future costs that they didn’t fully appreciate.

In aggregate,

nonfinancial companies’ cash flows over the past three years were

enough to cover capital spending. That is unusual—typically, capital

spending outstrips cash flows as companies invest for growth—and is

reflective of

how muted business investment has

been since the financial crisis. Over the same period, the companies

repurchased $1.3 trillion in shares.

Because those stock

buybacks helped reduce companies’ total shares outstanding, earnings

per share got a boost. Indeed, absent the past three years’

share-count reductions, S&P 500 earnings per share would have been 2%

lower in the fourth quarter than what companies are reporting,

according to S&P Dow Jones Indices.

The major reason

companies plowed money into buybacks rather than capital spending was

that, in a low-growth environment, the returns from investing in

expansion didn’t seem as attractive as in the past. This is a big part

of why companies were able to borrow cheaply: In a low-growth,

low-inflation environment, investors were willing to accept lower

returns on corporate bonds than if the economy was moving at a more

rapid clip.

The sticking point is

that in a low-growth environment, paying down debt also may be harder.

Especially because companies weren’t putting the money they borrowed

into capital investments, which provide cash flows to help service

debt. The stock they bought back won’t do that for them.

Even if this doesn’t

present an immediate problem for all companies given how they

refinanced debt to longer maturities, it could be a long-term drag on

earnings.

Of course, if necessary,

companies could issue new equity to help meet debt payments. But

existing investors would get diluted.

In many cases, companies

have large cash reserves they could tap. This, too, has drawbacks. One

is that, in cases where the cash is overseas, it might be subject to

taxation before it could be used. Another is that companies’ cash

holdings are reflected in their shares. If their cash is diminished,

so is their share price.

Investors who cheered as

companies bought stock with borrowed money could end up blanching when

they see the bill.

Write

to

Justin Lahart at

justin.lahart@wsj.com

|